Thanks for visiting our blog! As a thank-you, enjoy 15% off your first order in our online Viking Shop with the discount code BLOG15.

Skalds and Norse Poetry

Imagine walking into a bustling bar on a Saturday night and telling a story that was so good that everybody stopped to listen for the next few hours. That was just what a skald could do. Skalds were the poets of the Vikings, and poetry and storytelling where the most-prized art forms in Norse culture. Poetry was considered a gift of Odin, the Allfather chief god of the Vikings, and just being a skald made a person part of the jarl upper class in their society.

Vikings lived extremely active lives. When not sailing the seas to trade and make war, their days were still consumed with deep sea fishing, hunting, farming, herding, wood harvesting and dozens of other forms of hard work. When they found downtime, they liked sports like swimming, wrestling, skiing and the like. But Scandinavia is in the extreme north of Europe, and the winters of the Viking homeland were lethally cold. During such times, much of life happened indoors, in the large, open-planned longhouses where extended family and friends gathered around the fire. This was true from the humblest farms in Iceland to the grandest mead halls of the kings in Denmark, Sweden, or Norway.

Vikings lived extremely active lives. When not sailing the seas to trade and make war, their days were still consumed with deep sea fishing, hunting, farming, herding, wood harvesting and dozens of other forms of hard work. When they found downtime, they liked sports like swimming, wrestling, skiing and the like. But Scandinavia is in the extreme north of Europe, and the winters of the Viking homeland were lethally cold. During such times, much of life happened indoors, in the large, open-planned longhouses where extended family and friends gathered around the fire. This was true from the humblest farms in Iceland to the grandest mead halls of the kings in Denmark, Sweden, or Norway.

This simple fact of life in their climate created the Norse value of hospitality, and it created the role of the skald. It was at the fireside that the stories of their gods and ancestors would be repeated, and events from their own lives would be shared. The Vikings had runes to write with, but they reserved this writing for exceptional purposes. Everything – even the laws of the land – were passed on by word of mouth. In this strong oral culture, the skald with his poetry and saga-telling was the capstone.

Poetry in Norse Mythology

The Vikings attributed skill in poetry to the gift of the god, Odin. Odin had stolen the Mead of Poetry from the giants (giants in Norse mythology are a kind of anti-god, like a Titan, not the dim-witted hulks of later English and German fairy tales). The story of how he did that is a grand adventure that involved a lot of violence, sex, and shape-shifting, and climaxes in Odin flying across the Nine Worlds as an eagle with a mouth full of mead and a wrathful giant in hot pursuit.

The Vikings attributed skill in poetry to the gift of the god, Odin. Odin had stolen the Mead of Poetry from the giants (giants in Norse mythology are a kind of anti-god, like a Titan, not the dim-witted hulks of later English and German fairy tales). The story of how he did that is a grand adventure that involved a lot of violence, sex, and shape-shifting, and climaxes in Odin flying across the Nine Worlds as an eagle with a mouth full of mead and a wrathful giant in hot pursuit.

The Mead of Poetry itself was brewed from the blood of the god, Kvasir, who was the offspring (in a way) of all the Aesir and Vanir gods. As the story goes, while Odin was making his get-away, drops of the mead mixed with his saliva fell to earth, and this is the source of all mediocre or poor-quality poetry. The truly gifted skalds, however, received a drink of Odin’s mead by the god’s unique blessing.

The Mead of Poetry itself was brewed from the blood of the god, Kvasir, who was the offspring (in a way) of all the Aesir and Vanir gods. As the story goes, while Odin was making his get-away, drops of the mead mixed with his saliva fell to earth, and this is the source of all mediocre or poor-quality poetry. The truly gifted skalds, however, received a drink of Odin’s mead by the god’s unique blessing.

Poetry was important enough to be the domain of another god, too. Bragi was the god of poetry and music and was thought to welcome slain warriors into Valhalla. Bragi is said to have runes inscribed on his tongue and is usually pictured with a harp. He is the husband of the goddess of spring and eternal youth, Idun. It is possible that Bragi was inspired by the real 9th-century skald, Bragi Boddason, who composed such fantastic and stirring poetry that Vikings believed he ascended to god-hood..

How Skaldic Poetry Worked

Today we think of poetry as pretty words that rhyme or words arranged in a way that elicits strong emotion but can be interpreted differently by everybody. While it is an integral part of English-language poetic heritage, skaldic poetry is not really like that. Skaldic poetry usually told a story. Sometimes, though, the primary purpose was to convey some spiritual mystery or hidden knowledge (for example, the Havamal, the Rune Poems, or the Grimnismol). Skaldic poetry was based on meter. Different types of meter were used (with varying levels of complexity), depending on what type of poem was being composed.

While the skald had to have a tremendous amount of knowledge and memory, skaldic poetry was not all about memorization and recitation. Much of the poetry was made up on the spot, tailoring the poetry to the inspiration of the moment, the mood, and the reaction of the audience. The skald would sometimes use a lyre or harp to keep time (see our article on Viking music here) as he extemporized based on his theme.

While the skald had to have a tremendous amount of knowledge and memory, skaldic poetry was not all about memorization and recitation. Much of the poetry was made up on the spot, tailoring the poetry to the inspiration of the moment, the mood, and the reaction of the audience. The skald would sometimes use a lyre or harp to keep time (see our article on Viking music here) as he extemporized based on his theme.

The skald also used lyrical forms called kennings to both color his poem and buy him some time to find his artistic path. Kennings were premeditated phrases and allusions that described things obliquely, such as referring to Odin as “Fenrir’s Enemy” or Thor as “the Troll-wife’s grief,” or to gold as “Otr’s ransom.” These phrases (and others that are much more complicated) could be dropped in appropriate places to add depth and to ensure the audience stayed engaged. Skalds loved to up the complexity so that the hearers that knew the most lore got the most out of the poems, and the audience loved to compete with each other in the same way.

Here is a brief example of both the verse structure and kennings, provided by Brown (2012) from the Voluspa (sometimes called, Song of the Sibyl) from the Poetic Edda:

I know for certain Odin

Where you conceal your eye

In the famous Spring of Mimir

Mead he drinks

Every morning

From the Pledge of the Father of the Slain

Do you know any more or not?

The speaker here is the Völva (the seeress or prophetess) and is referring to Odin sacrificing his eye to drink from the Well of Urd and thus gain wisdom.

Using these methods, every time a skald performed his poetry was different, and though the audience knew most stories by heart, they never heard them the same way twice. Skaldic poetry has been compared to jazz or the fugues (endless variations on a theme) of classical music. This quality of creativity and inspiration inherent in skaldic poetry is probably the biggest reason why the poems were not written down. They were living creations.

The Life of a Skald

Like the Celtic druids, an aspiring skald would have to begin his or her training early to forge their memory, hone their skills, and develop their talent. While the poetry itself was not the product of extensive memorization, the vast body of mythology, history, lore, kennings, and the essential family lineages had to be learned. The best skalds spent a lifetime perfecting their art.

Though a skald was considered a member of the jarl (aristocratic) class, many of them were itinerant and had little to call their own. They traveled from hall to hall, accepting the hospitality of their hosts in exchange for the entertainment (and education) they provided.

Whether in the longhouse of the farmer or the mead hall of the king, the skald was met with an eager and discerning audience. If the skald had skill and talent, his listeners would hang on his words, but if he were having a bad night or was fudging his material, they would know and would not be impressed. In the Viking world, having an appreciative audience did not always mean having a quiet audience, and the sagas tell a few instances of fights breaking out in the middle of a skald’s recital.

Skalds were a diverse lot. Jórunn Skáldmær (Jórunn “Poet-maiden”) was one example of a female skald in 10th century Norway. Some skalds like Egill Skallagrímsson and Gunnlaug Snake-Tongue were world-traveling Vikings themselves who always wound up in the middle of dramatic action and became the subjects for other poets to compose about.

While some skalds could be Vikings, many Vikings could be poets, too. Anyone who knew some poetry was welcome on a longship, where the beat of the oars on the water could keep time as the words kept the warrior’s spirits as buoyant as the ship and full as the sails. The 11th-century super-Viking, Harald Hardrada accepted the surrender of 80 cities, but when it came time to boast, he boasted that he could compose poetry. Vikings would recite poetry before going into battle to inspire them towards glory.

An example of this type of fighting poem is this verse from the Krákumál (here in Percy’s 1763 English translation):

We fought with swords,

before Boring-holmi.

We held bloody shields:

we stained our spears.

Showers of arrows brake the shield in pieces.

The bow sent forth the glittering steel.

Volnir fell in the conflict,

than whom there was not a greater king.

Wide on the shores lay the scattered dead:

the wolves rejoiced over their prey.

The Viking Age (793-1066) was a massive boon for the skalds and a new golden age of skaldic poetry for two reasons. The first reason is that there were now many more great deeds and fantastic events to compose poetry about. The second reason was that the influx of wealth the Vikings brought in meant that there were many more patrons, and better venues for the skalds to perform their art. This proliferation and strengthening of the art form are evident in that skaldic poetry survived well enough for men like Snorri Sturluson to write it down more than a hundred years later.

Like the musicians of today, a skald could earn great wealth or barely make a living. Wherever they went, though, skalds were received with great honor – not only out of respect for their art but because, like the gods, the last thing you wanted to do was make a poet angry. They were the reputation makers of the day, and it has been said, “the greatest heroes have the greatest poets.”

If you would like to learn more about the Vikings, their adventures, lore, history, culture, and times, check out our book, Sons of Vikings by David Gray Rodgers and Kurt Noer.

If you would like to learn more about the Vikings, their adventures, lore, history, culture, and times, check out our book, Sons of Vikings by David Gray Rodgers and Kurt Noer.

https://sonsofvikings.com/products/viking-history-book

Image Sources

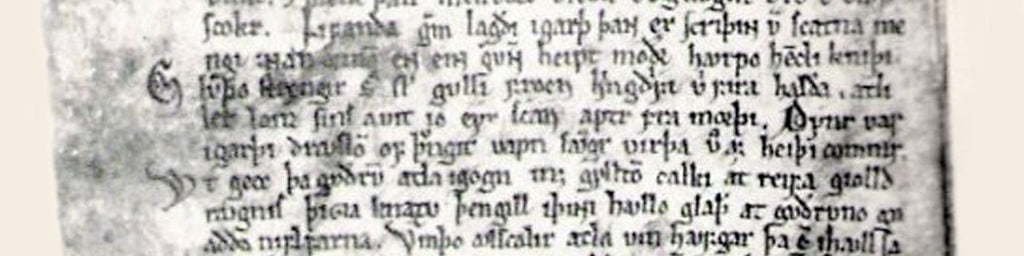

Poetic Edda page: https://norse-mythology.org/sources/

Stora Hammars Stone: https://norse-mythology.org/tales/the-mead-of-poetry/

Chased by Suttungr illustration: 18th century Icelandic artist Jakob Sigurdsson. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mead_of_poetry#/media/File:Processed_SAM_mjodr.jpg

Bragi painting: 19th century artist Nils Blommer. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bragi

References

- Rodgers, D. & Noer, K. Sons of Vikings: History, Legends, and Impact of the Viking Age. KDP Press. 2018.

- Harl, K. Vikings: The Great Courses. The Teaching Company, Chantilly, VA. 2005.

- Brown, N.M. Songs of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of the Norse Myths. Palgrave MacMillan, New York. 2012.

- McCoy, D. Norse Mythology for Smart People. 2019. https://norse-mythology.org/gods-and-creatures/the-aesir-gods-and-goddesses/bragi/

- McCoy, D. The Mead of Poetry. Norse Mythology for Smart People. 2019. https://norse-mythology.org/tales/the-mead-of-poetry/

- McCoy, D. What is a Kenning? Norse Mythology for Smart People. 2019. https://norse-mythology.org/what-is-a-kenning/

- Percy, T. Krákumál. translated 1763. https://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/norse/HTML/Percy.html

About Sons of Vikings

If you appreciate free articles like this, please support us by visiting our online Viking store and follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Share this article on social media: