Thanks for visiting our blog! As a thank-you, enjoy 15% off your first order in our online Viking Shop with the discount code BLOG15.

Consider how the bible, a collection of 66 different "books" (ancient written documents) offers a deeper understanding of the history relating to early Jews and Christians, those of us who are Scandinavian descendants or even anyone interested in Vikings and Norse mythology have asked, "What kind of ancient written documents do WE have?"

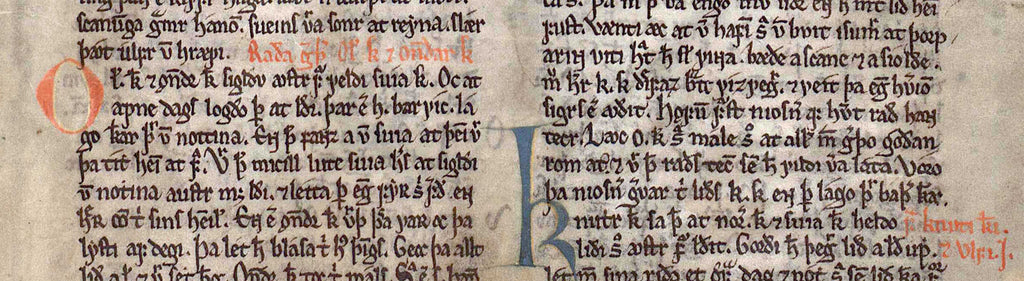

The answer is the Icelandic writings known as the Sagas and Eddas. While some have turned portions of these documents into "scripture" (to support the worship of ancient Germanic spirits and gods), most people see these 12th and 13th century writings as the closest thing we have to ancient written accounts of Norse mythology and Viking history.

Edda

/ ed-uh /

noun

Either of two 13th-century Icelandic books, the older 'Poetic Edda' (a collection of Old Norse poems on Norse legends) and the younger 'Prose Edda' (a handbook to Icelandic poetry by Snorri Sturluson). The Eddas are the chief source of knowledge of Scandinavian mythology.

saga(s)

/ sah-guh /

noun

One of many long stories of heroic achievement focusing on Norse, Icelandic and Viking related history and folklore, recorded in Iceland during in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Vikings came from a rich cultural heritage of storytelling and poetry. The poet was one of the most respected persons in Norse society and could always expect wealth and welcome in exchange for their talents. Even Odin – the Allfather and the chief of the Aesir gods – was a god of poetry. The tales of gods, heroes, and history found perpetual life in the mead halls of the Vikings. ...however, the Vikings never wrote any of it down.

The Vikings had runes, which served as both letters and glyphs for specific meanings. However, runes had ceremonial or even magical purposes. Vikings had no intention of using these sacred conduits to the gods for writing stories. No – the tremendous oratory and lore of the Vikings were meant to be passed on from person to person with the human voice.

Viking lore might have fallen by the wayside and been lost to the mists of history, had it not been for a unique intellectual phenomenon in Iceland a century or more after the last Vikings died.

How Iceland Saved Viking Lore

A majority of the written sources we do have are from Iceland. Vikings discovered Iceland in the middle of the 9th century. This discovery led to a land rush as many families were eager to carve out a new life in this austere place of stark beauty. Many of these settlers were escaping Harald Fairhair and other despotic kings who were nation-building in Scandinavia. These pioneer families were fiercely independent and wanted to preserve their way of life and culture without becoming the serfs of greedy lords.

A majority of the written sources we do have are from Iceland. Vikings discovered Iceland in the middle of the 9th century. This discovery led to a land rush as many families were eager to carve out a new life in this austere place of stark beauty. Many of these settlers were escaping Harald Fairhair and other despotic kings who were nation-building in Scandinavia. These pioneer families were fiercely independent and wanted to preserve their way of life and culture without becoming the serfs of greedy lords.

Consequently, many of the Vikings who settled Iceland were from western Norway. Other Vikings came to Iceland indirectly, by way of the Hebrides, Orkney, Ireland, or the Faroe Islands, with Celts from those lands making up portions of their households.

The Vikings set up a democracy in Iceland, with a firm sense of law based on honor and restitution. In the year 1000, the Icelanders voted to accept Christianity as the public religion, while allowing people to practice whatever religion they chose in private. This decision was made for the sake of peace and to keep up with the changing times. But this peculiar conversion would have another effect as well: while Viking descendants in Christianized Scandinavia, Normandy, England, and elsewhere actively distanced themselves from their pagan past, the Icelanders were much more comfortable with that part of their heritage. This, combined with natural isolation and a conservative disposition, led to Iceland remaining a bastion of Old Norse culture.

Even today, a thousand years later, the modern Icelandic language is very similar to Old Norse. Though some word meanings and pronunciation have naturally shifted, Icelandic college students can read the Medieval manuscripts without much difficulty. This retention of language is a tremendous testament to the cultural preservation that occurred in that island nation.

In the middle of the 13th century – more than 150 years after the last Vikings sailed the seas or stood in battle – Iceland was undergoing a violent political crisis. This crisis of politics became a crisis of identity, and perhaps because of this, there was a strong intellectual impulse to record the remnants of their ancient heritage. For the first time, Viking lore was set down in writing for future generations to read.

This creative impulse expressed itself in two forms: The first was the Eddas – the collected poetry and myths of the Old Norse gods, goddesses, and heroes. But the second impulse may have been the more remarkable: the Icelanders set down the stories of their ancestors – ordinary men and women. These sagas were a unique accomplishment in medieval literature. Even today, the sagas are recognized as one of the world’s great literary achievements and a forerunner of the modern novel.

Even in the Viking Age, poets from Iceland were considered among the best. But after their time, their descendants expanded the Norse oral tradition into a vibrant literary culture. To this day, Icelanders read more books and even write more books per capita than any other nation in the world.

A Remarkable – but Imperfect – Recollection

The Eddas and sagas powerfully demonstrate the strength and vigor of the Norse oral tradition. The poems are remembered so faithfully that modern scholars can determine the time and place in which each one was originally composed based on their wording, grammar, and syntax. Though there are many contradictions in the literature, there is also incredible cohesion. For example, in The Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson mentions Thor’s feet crashing through the bottom of the fishing boat as he angled for the Midgard Serpent known as Jörmungandr. This same curious detail is depicted on the Altuna runestone (as seen to the right). This runestone was carved hundreds of years before and hundreds of miles away in Sweden – a stone Snorri was unlikely to have ever seen. Proving that these stories had united Vikings across vast distances of time and space.

For example, in The Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson mentions Thor’s feet crashing through the bottom of the fishing boat as he angled for the Midgard Serpent known as Jörmungandr. This same curious detail is depicted on the Altuna runestone (as seen to the right). This runestone was carved hundreds of years before and hundreds of miles away in Sweden – a stone Snorri was unlikely to have ever seen. Proving that these stories had united Vikings across vast distances of time and space.

Despite this precision and cohesion, there are limitations to the surviving body of Norse literature. A lot of it is missing. The Eddas mention that there were 12 or more gods and 12 or more goddesses – but most of our stories rotate around about 10 (total), with three or four superstars. The scribes compiling The Poetic Edda had to use prose narratives to join the surviving fragments together. It is difficult to determine how much Norse lore is lost to us, but it seems that we only have a small percentage of what once was.

Another limitation is bias. The revival of Norse lore that took place in Iceland in the 13th -14th centuries was the preservation of heritage, and not a pagan revival. The Christian compilers and writers of the sagas and Eddas took a range of attitudes towards the faith of their ancestors.

For example, in The Prose Edda, Snorri states the Aesir were not gods at all but were heroes traveling to Scandinavia from ancient Troy. Snorri elaborates on this theme in his Ynglinga Saga. This was a popular convention amongst medieval historians to try to tie their past to ones that were more widely valued in Europe. This objective accomplished, a few pages later in the Prose Edda, Snorri abandons this narrative and goes back to calling the Aesir and Vanir gods, depicting them creating the world, and performing other supernatural feats.

For example, in The Prose Edda, Snorri states the Aesir were not gods at all but were heroes traveling to Scandinavia from ancient Troy. Snorri elaborates on this theme in his Ynglinga Saga. This was a popular convention amongst medieval historians to try to tie their past to ones that were more widely valued in Europe. This objective accomplished, a few pages later in the Prose Edda, Snorri abandons this narrative and goes back to calling the Aesir and Vanir gods, depicting them creating the world, and performing other supernatural feats.

Even in The Poetic Edda, there are a few verses that may be Christian revisionism. Similarly, in the sagas written in later times, berserkers – with their highly pagan connotation of devotion to Odin – are usually portrayed as evil brutes.

The great majority of surviving Norse literature comes from Iceland, so we should not be too surprised to find it has a pro-Icelandic slant. Since most Icelanders were from Norway and the various Viking ports in Ireland, Scotland, etcetera, these places are also portrayed favorably. Meanwhile, many mentions of Sweden and the Baltic are negatively charged, sometimes even described as “Mirkwood” and a dark land of dragons, dwarves, giants, and savage men. Many of the villains in the sagas are Swedish Vikings. It is important to remember that the Vikings settled in numerous regions and adapted to conditions there. So, while Viking Age Iceland may be a model Norse culture, it is not the only version of Norse culture.

The Prose Edda

The Prose Edda was written around 1222 by Snorri Sturluson, the "Homer of the North." Snorri was an Icelandic politician credited with Egil’s Saga and the Heimskringla (History of the Kings of Norway). Snorri seems to have deliberately written The Prose Edda as a guide for the preservation and continuation of Norse poetry. Modern readers should not let this “textbook” designation deter them, though: The Prose Edda is am extremely accessible, concise work of about 100 pages that offers the most complete survey of Norse lore available.

The Prose Edda was written around 1222 by Snorri Sturluson, the "Homer of the North." Snorri was an Icelandic politician credited with Egil’s Saga and the Heimskringla (History of the Kings of Norway). Snorri seems to have deliberately written The Prose Edda as a guide for the preservation and continuation of Norse poetry. Modern readers should not let this “textbook” designation deter them, though: The Prose Edda is am extremely accessible, concise work of about 100 pages that offers the most complete survey of Norse lore available.

No one is sure what the term "Edda" means, or why Snorri named his work that. "Edda" was a colloquial Icelandic term for great-grandmother, and so it may be that Snorri was emphasizing the element of heritage in Norse lore. The term stuck, and not only was the later collection of poems called “The Poetic Edda," but all Norse poetry has come to be known as "eddic poetry.” It is, of course, also called “skaldic poetry” after the Norse bards or skalds.

The Poetic Edda

The Poetic Edda is a collection of about three dozen very old Norse poems. The volume is not every surviving Norse poem, but it is the most extensive collection. The Poetic Edda presents in the fullest and most complete available way what the Viking oral tradition was all about. The Poetic Edda was first collected in one book around 1270 – almost 50 years after The Prose Edda. It is still sometimes called The Elder Edda because the poetry dates back to the 9th, 10th, and early 11th centuries, and some of the source-material may go back even further.

The works collected in The Poetic Edda fall into two categories: poems of gods and poems of heroes. The poems of gods offer some of the best collections of Norse mythology, with most of the major stories being represented: the creation of the world, Ragnarok, the battle of the Aesir and the Vanir, Thor’s fishing for the Midgard Serpent, and many others. Meanwhile, the heroic poems are primarily concerned with human (or sometimes elf or dwarf) protagonists. Many of these works elaborate on The Volsung Saga, in much the same way that modern people are always making prequels, sequels, and reboots of our favorite movies.

A seated bronze statue of Thor (about 6.4 cm) known as the Eyrarland statue from about AD 1000 was recovered at a farm near Akureyri, Iceland and is a featured display at the National Museum of Iceland. Thor is holding Mjöllnir, sculpted in the typically Icelandic cross-like shape. It has been suggested that the statue is related to a scene from The Poetic Edda where Thor recovers his hammer while seated by grasping it with both hands during the wedding ceremony.

A seated bronze statue of Thor (about 6.4 cm) known as the Eyrarland statue from about AD 1000 was recovered at a farm near Akureyri, Iceland and is a featured display at the National Museum of Iceland. Thor is holding Mjöllnir, sculpted in the typically Icelandic cross-like shape. It has been suggested that the statue is related to a scene from The Poetic Edda where Thor recovers his hammer while seated by grasping it with both hands during the wedding ceremony.

When The Poetic Edda was first translated into English in the 1800s, an effort was made to make the pieces overly formal and flowery like Greco-Roman poetry. Today, newer translations keep the blunter, more straightforward style of the original. One of the best ways to appreciate The Poetic Edda is not to read it, but rather to listen to it on Audiobooks or other platforms. The poems, after all, were meant to be recited and heard.

Famous Eddic Poems

There are about three dozen poems in The Poetic Edda. Here are a few of the more widely appreciated ones.

Voluspa and Voluspa en skamma

Both Voluspa (The Song of the Seeress or The Song of the Sybil) and Voluspa en skamma concern Odin's conjuring of a witch's ghost to try to gain insight into how he might forestall Ragnarök, the terrible end of the world.

Both Voluspa (The Song of the Seeress or The Song of the Sybil) and Voluspa en skamma concern Odin's conjuring of a witch's ghost to try to gain insight into how he might forestall Ragnarök, the terrible end of the world.

Through the poems, the volva sorceress describes the epic fate of the gods including the final battle between Thor and the serpent Jormundandr, the final battle between Odin and the Norse wolf Fenrir and the final battle between Loki and Heimdall (the guardian of Bifrost, the rainbow bridge). She discloses to the hearer many other secrets of the Norse cosmos. These dark poems are full of awe and essential for understanding the Viking view of fate.

Grimnismal and Vafthrusnismal

Both Grimnismal and Vafthrusnismal tell stories of Odin traveling the world in disguise and gradually revealing his divine nature to his unlucky hosts. These plots form a frame for much of Norse cosmology and lore to be revealed, including tales of Valhalla and Yggdrasil.

Havamal

Havamal (Sayings of the High One) is a long poem that may have once been four different poems. It is words ascribed to Odin himself. The chief of gods reveals much about his nature and abilities but spends most of the poem giving the listener down-to-earth advice. Because of its format, Havamal is sometimes referred to as the Vikings’ “Book of Proverbs” and strikes many modern people as a sort of “Viking scriptures.” Havamal offers a fascinating view of Viking ethics and ethos and gives the reader more wisdom with each reading.

Rigsthula

Rigsthula is the tale of the god, Heimdall, traveling in disguise through Middle Earth, and interacting with humans. On the surface, the story is bawdy and comical – but Rigsthula uses these metaphors to describe social order and to offer a grim warning to the dangers of concentrated political power. As such, Rigsthula is one of the most striking and “most transparent sociological commentaries of its time” (Crawford, 2015).

Lokasenna

Norse mythology is loved for the uniquely human qualities of its gods and goddesses. In Lokasenna – The Taunts of Loki – the Viking god of mischief and treachery crashes a divine drinking party and brazenly confronts each of the gods with their deepest darkest secrets.

The Norse Saga

The Norse word “saga” comes from the word for “saying.” These stories were the oral histories of families passed on from fathers to sons and mothers to daughters. Indeed, the style of the Norse saga conveys this form of a meandering, straightforward, unembellished story. Anyone who has had the privilege of leisurely discourse with grandfathers or older, extended family will immediately recognize the nature of these narratives.

When they were written, the style and scope of the sagas were highly unusual. The currency of medieval literature was formal poetry, and the subject matter was usually tales of kings, saints, or other elites. Yet in Medieval Iceland, a literary form emerged that was prose, and – more remarkable still – many of the protagonists were largely ordinary people such as farmers, lawyers, women, warriors, poets, slaves, or outlaws.

In this way, the Norse saga predicted the modern novel and has many similarities. But unlike the modern novel, where an author tries to develop a unique "voice," the Norse saga has a very straightforward narrative style. This style is seemingly at odds with the Norse poetry style with its hyperbolic action and emotive kennings. While modern writers try to all sound different, Norse saga writers tried to all sound the same, and while skaldic poetry tried to amp-up the drama of their tale, Norse sagas use a stripped-down style to emphasize plot.

Genres

Norse sagas come in several genres. Of these, three most concern the Viking enthusiast: the heroic/legendary sagas (fornaldarsögur), the historic/kings’ sagas (konungasögur), and the “sagas of the Icelanders” or “family sagas” (Íslendingasögur). The legendary sagas are stories of gods and heroes set in the distant, murky past. They are full of dragons, werewolves, and fantastic elements. The king's sagas set down the lives of rulers and historical events that shaped the Viking world but include dialogue and other dramatic elements to bring these stories to life.

The family sagas, by contrast, tell the stories of real Icelanders. While these stories usually have plenty of fighting and Viking raids, they are not exclusively about that. Family sagas are about human relationships, the struggles of survival in a stark land, and a surprising amount of legal drama. Through the family sagas, one gets to appreciate the complexity of Viking life, the depth of these people's intelligence and strength, the richness of their culture and quality of their lives.

The Sagas as History

The sagas are the collective memory of a people written down lifetimes after the events they describe. Therefore, one must be cautious in using them as a historical source. Some experts go so far as to label the sagas “historical fiction” or to warn us that using them as history would be like using John Wayne movies as a source for your college paper on World War II. Such criticism may be going too far. Certainly, the sagas vary in terms of historical accuracy and/or historical merit (i.e., how much truth they add to the historical picture). Yet, because of the detail one finds in sagas that one could not find anywhere else, they are essential to understanding what happened, why, and ultimately what it felt like to the people who lived it. The sagas are not necessarily history as facts and sequences, but rather history as experiences remembered.

Famous Sagas

There are many sagas, including about 40 family sagas. Here are a few of the most famous, over various genres.

The Volsungs’ Saga

Sometimes referred to as “the Iliad of the North,” The Volsung’s Saga (Volsungasaga) is the archetypal legendary saga. There is ample evidence that this was the Viking’s favorite story. Along with its contemporaneous continental cousin, The Nibelungenlied, The Volsung’s Saga has directly or indirectly influenced almost every western fantasy since, from Wagner’s operas and Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, to Star Wars and Game of Thrones. The Volsung’s Saga is a story of a cursed treasure, and how this treasure ruins the lives of the people who claim it, culminating in a blood feud between the best of friends.

The Volsung’s Saga is set in the early-middle 5th century when Goths and Huns battled for survival and supremacy. But despite a cameo by Attila the Hun, The Volsung’s Saga is a work of high fantasy. It has almost every conceivable element: dragons, dwarves, spirits, shape-shifters and werewolves, divine intervention, forbidden love, orphaned heroes, revenge, madness, suicide, betrayal, murder, blood oaths, chosen ones, fratricide, superheroes, prophecies, talking animals, cannibalism, incest, Valkyries, inexorable fate, rune lore, sleeping beauties, intrigue, magic weapons, and lots of sex and violence.

This tale was so popular amongst many Nordic/Germanic peoples for many centuries that it generated several versions. Volsungasaga is the Icelandic version and follows the Volsung family primarily. The Germans wrote a somewhat more Christianized and romanticized version called The Nibelungenlied that followed the Nibelung family. As already mentioned, The Poetic Edda contains many poems that elaborate on the tale.

The Saga of Hrolf Kraki

The Saga of Hrolf Kraki is not quite as famous or as influential as the Volsung’s Saga, but it is a deep source of legend. Hrolf Kraki is a Scandinavian warlord who gathers a group of extraordinary heroes around him to right wrongs and attain glory. Thus, Hrolf Kraki is something of a Viking version of King Arthur, complete with an epic, tragic ending. The Saga of Hrolf Kraki also contains an alternate, Viking version of the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf tale. The legendary sagas like Hrolf Kraki are so old and so embellished that they only contain the specter of real history, but recently archeologists have uncovered sites in Denmark that seem to match up with some episodes in the Hrolf Kraki story.

The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok and His Sons

Ragnar Lothbrok is one of the most famous Vikings of all time, with mentions to him and his sons throughout sagas, poems, and even non-Viking sources (like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok and His Sons (Ragnars saga lodbrokar) is the most complete saga form of his story. Ragnar’s saga has legendary elements (like a magical serpent/dragon, curses, improbable genealogies, and protection charms) but is set just before the founding of Iceland and has many verifiable historical details. This saga is the main source for the first few seasons of the TV show Vikings. The saga presents Ivar the Boneless as physically disabled (while most other sources do not mention that). Unlike the TV show, the saga does not include Lagertha. Lagertha appears as Ragnar’s shieldmaiden wife in Saxo Grammaticus’s 13th-century Gesta Danorum, a multi-volume history written in Denmark.

Egil’s Saga

Egil’s Saga is probably the best of the Icelandic family sagas for Viking enthusiasts. Set in Norway, Iceland, and England from about 850-1000, the saga tells the story of the Skallagrim clan. The central hero is Skallagrim’s son, Egil, the quintessential Icelandic Viking – a farmer, raider, businessman, soldier, bodyguard, avenger, lover, father, lawyer, and of course an accomplished poet. Egil travels the North Atlantic in search of adventure and trying to stay one step ahead of Erik Bloodaxe (the real-life Viking king of York) and his wrathful witch wife. Egil’s Saga balances some over-the-top violence with intelligence and artistry, giving a full view of what it was like to be a 10th century Viking.

Njal’s Saga

Njal’s Saga is one of the most highly-developed and respected of all the Icelandic sagas. It is considered by many to be a literary masterpiece, and more 13th-14th century manuscripts survive than any other saga. The central character, Njal, is a man of peace who is highly respected for his wisdom, but even this is not enough to keep him and his family safe from the bloody feuds fate sends their way. Njal’s Saga has some excellent and memorable fight scenes, but most of the drama arises from the relationships between the many characters. The saga covers the Christian conversion of Iceland in 1000, and the cataclysmic Battle of Clontarf, which closed the Viking Age in Ireland in 1014. It also gives an unparalleled view of Norse law and politics.

The Laxdale Saga

The Laxdale Saga (also called Laxdæla Saga or The Saga of the People of Laxárdalr) may have been the second most popular family saga during the Middle Ages, based on the number of surviving manuscripts. This may be surprising, considering that the Laxdale Saga is no tale of bloody adventure like The Saga of the Volsungs or Egil’s Saga. The Laxdale Saga is the story of several families settling in Iceland, and the tragic love triangle that arises between a woman, Gudrun, and two best friends, Kjartan and Bolli. As usual, there is plenty of travel, politics, feuds, and honor at stake, but The Laxdale Saga is a complex, sentimental tale of love, loss, and regret. Some experts believe this saga may have been written by a woman, due to the uncommon perspective. There were female skalds (poets and storytellers) in Viking Age Scandinavia, so perhaps there were in post-Viking Iceland as well.

The Saga of Gisli Sursson

The Saga of Gisli Sursson is an example of how Icelandic saga writers moved away from the canned tales of heroes that most of their age was preoccupied with, to cover real people with real moral dilemmas. The protagonist, Gisli, finds himself honor-bound to kill one brother-in-law to avenge another brother-in-law. Gisli then spends many years as an outlaw, running from men who are sworn to kill him.

The Saga of Grettir the Strong

Like The Saga of Gisli Sursson, Grettir’s Saga is an outlaw saga. The namesake character, Grettir, is a young man naturally gifted with great strength and boldness to the point that he is almost like a mortal version of Thor. But unlike Thor, Grettir has streaks of stubbornness, recklessness, cruelty, and an inability to fit in that spoils his relationships with other people and ultimately lead to him living the life of an outcast.

Like The Saga of Gisli Sursson, Grettir’s Saga is an outlaw saga. The namesake character, Grettir, is a young man naturally gifted with great strength and boldness to the point that he is almost like a mortal version of Thor. But unlike Thor, Grettir has streaks of stubbornness, recklessness, cruelty, and an inability to fit in that spoils his relationships with other people and ultimately lead to him living the life of an outcast.

Grettir’s hero/anti-hero nature gives a modern, Tarantino-like feel to this saga. The Saga of Grettir the Strong also has many supernatural elements (like ghosts, witches, miracles, and zombies) but maintains a sort of “magical realism” tone. While some – or even all – of this saga may be fictitious, today in Iceland, there are many physical sites connected to Grettir and his feats.

The Vinland Sagas (the Saga of Erik the Red and the Greenlander’s Saga)

Perhaps no sagas have as much interest to modern readers as the Vinland Sagas. Both The Saga of Erik the Red and The Greenlander’s Saga tell the story of the founding of Greenland (around 985) and the Viking exploration of the American continent around the year 1000. The two sagas disagree with each other on some details, and struggle to convey the wonders that were passed down by word-of-mouth over all those intervening years. But here are written accounts of lands to the far west, complete with indigenous peoples, written hundreds of years before Columbus. Viking sites consistent with these sagas have also been discovered and substantiated in Newfoundland, off the coast of Canada. Being right about North America lends credibility to the Norse sagas in general. You can read more about the Vinland Sagas in our four-part series on them here.

Conclusion

Norse literature is the extension of Norse oral tradition and is one of the richest and most imaginative of cultural heritages anywhere. We are lucky that this body of work has survived and been passed down to us, and indeed it has influenced so many people in so many ways. We encourage the reader to try these fantastic poems, stories, and books to gain a fuller experience of this art and to be edified by the men and women who came before us. The lives, loves, and wisdom of the past can lead to better understanding and appreciation of what humanity shares regardless of time or distance.

.

Sons of Vikings is an online store offering hundreds of Viking inspired items, including Viking jewelry, Viking clothing, Drinking horns, home decor items and more.

To learn more about Viking history, we recommend our 400+ page, self titled book that is available here.

Image Sources: Wikipedia

References

- Volsunga Saga (the Saga of the Volsungs). Crawford, J. (translator). Hackett Classics. 2017.

- The Poetic Edda. Crawford, J. (translator). Hackett Classics. 2015.

- Egil’s Saga (Egils saga Skallagimssonar). Scudder, B. (translator). In The Sagas of the Icelanders (editor, Thorson, O. & Scudder, B.) Penguin Books, New York, 2001.

- The Saga of Hrafnkel Frey’s Godi. Gunnel, T. (translator). In The Sagas of the Icelanders (editor, Thorson, O. & Scudder, B.) Penguin Books, New York, 2001.

- Gisli Sursson’s Saga. Regal, M. (translator). In The Sagas of the Icelanders (editor, Thorson, O. & Scudder, B.) Penguin Books, New York, 2001.

- The Galdrabok: An Icelandic Grimoire. Flowers, S. (translator) Baker Johnson, Inc. Ann Arbor, MI. 1989

- The Saga of Grettir the Strong. Scudder, B. (translator). Penguin. London. 2005. Snorri Sturluson’s The Prose Edda. Translated with introduction by J. Byock. Penguin Books, London. 2005.

- Brown, N.M. Songs of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of the Norse Myths. Palgrave.MacMillan, New York. 2012.

- Saxo Grammaticus. The Danish History, Book Nine. Circa 12th Century. Retrieved January 4, 2018, from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1150/1150-h/1150-h.htm

- The Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok and His Sons (Ragnar Saga Lodbrok). Waggoner, B. (translator). Troth. 2009

- The Lay of Harold (Hranfnsmol). Hornklofi, T. (translator). Sacred Texts. https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/onp/onp11.htm

- The Saga of Erik the Red. Sephton, J. (translator). 1880. Accessed August 16, 2018. http://sagadb.org/eiriks_saga_rauda.en

- The Settlement of Iceland: Ari Frodi (Landnámabók). Ellwood, T. (translator). 1898. Accessed December 23, 2017. https://ia801406.us.archive.org/29/items/booksettlementi00ellwgoog/booksettlementi00ellwgoog.pdf

- The Heimskringla of Snorri Sturluson (Haralds saga ins hárfagra). Finley, A. & Faulkes, A. (translators). Viking Society for Northern Research. London. 2011. Accessed December 23, 2017. http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Heimskringla%20I.pdf

- The Book of the Icelanders (ÍSLENDINGABÓK). Finley, A. & Faulkes, A. (translators). Viking Society for Northern Research. London, 2006. Accessed December 23, 2017. http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Text%20Series/IslKr.pdf

- Rodgers, D. & Noer, K. Sons of Vikings: History, Legends, and Impact of the Viking Age. United States. 2018.