Thanks for visiting our blog! As a thank-you, enjoy 15% off your first order in our online Viking Shop with the discount code BLOG15.

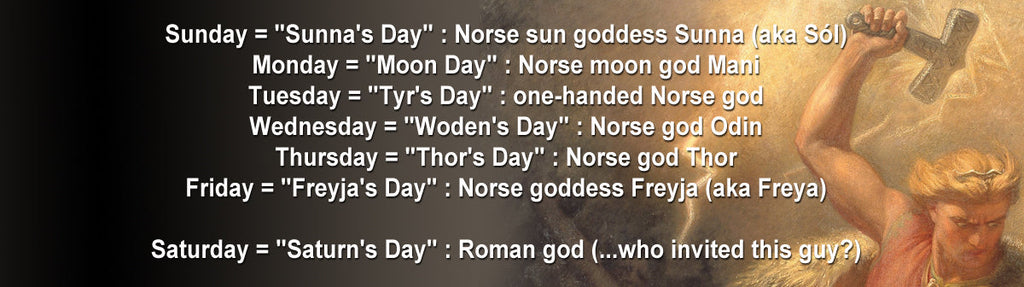

Many people know that our names for the days of the week carry the memories of ancient gods. And while the Romans had their own official names for each day of the week, the gods of Norse mythology have a very strong presence in the day names we use today. For example, Thursday comes from Thursdaeg or Thorsdagr (Old Norse: Þórsdagr), which means "Thor's day".

It is uncertain when or where theophoric naming of days began but there is good evidence that it originated in the Mediterranean with the Greeks or Romans. However, it could be older than that. It is also uncertain whether the Vikings, Saxons, and other Northern peoples acquired this habit from contact with Romans or if they had been doing the same thing independently. One thing is clear from the evidence left to us: the names of days in English tell a story of cultural blending and offers a small paradox of change and continuity. This may seem like a lot of information to derive from seven simple names, but read on and see what we mean.

Sunday

Arguably, the sun is the most essential thing for life on this planet. So, it comes as no surprise that ancient cultures either worshiped the sun directly or made sun gods key members of their pantheons. The Egyptians had Ra. Apollo was worshiped across the Mediterranean. Later, Roman rulers tried to make Sol Invictus (the Invincible Sun) the official god of the Empire. So, it is no surprise that the Romans named the first day of the week Dies Solis (Sun Day). However, in later Romance languages (like Spanish, French, or Italian), the name changed to reflect Catholic culture (i.e., domingo/domenica/dimanche).

The Vikings seem to have had a different view, though. In Norse belief, the sun was not some powerful masculine god. Instead, the sun was a woman (a goddess presumably, but never expressly called that). This woman, Sunna or Sól, drives her chariot lit from the sparks of Muspellsheim (the land of fire) across the sky (i.e. Sunna's Day or Sun Day). Sól's horses are called Arvak and Alsvinn, and they are cooled by bellows under their shoulders. Sól is continuously pursued by a giant wolf named Skoll, who is a relative of Fenrir.

There is significant archeological evidence that there was once a prominent cult of the sun in Scandinavia. However, almost all of these monuments and solar symbols faded away in the 6th century. This coincides with a great time of famine, frost, and darkness in the north that decimated the population and shattered people's way of life. This little ice age was caused by two volcanic eruptions around the 540s. Some archaeologists theorize these catastrophes discredited the sun cult, driving the survivors of those grim decades to alter their faith. So, by the time of the Vikings some three centuries later, the Norse had no significant sun deity – just a woman fleeing from wolves. Many of the fertility and prosperity features one would expect from a sun deity were (apparently) transferred to gods and goddesses like Freyr or Sif.

Monday

Monday was the day the Romans devoted to the moon. In modern romance languages, it is rendered lunes/lundi/ lunedì. For the Romans, the moon was associated with goddesses like Diana/Artemis, Selene, and Hecate. Once again, the Vikings saw this the other way. The moon was Máni, Sól's brother (i.e. Moon Day). Like his sister, the Sun, Máni rode a chariot across the sky and was pursued by wolves. At Ragnarok, Fenrir's brood is fated to devour the moon. This ominous portent is often mentioned in the Eddic poems.

As with Sól, Máni seems like a personification to explain a natural phenomenon and does not seem to hold much importance in the Viking pantheon – unlike the weighty significance Mediterranean peoples placed on their moon goddesses. These tales of wolves devouring the sun and moon may have been inspired by the terror the ancients felt when viewing an eclipse.

Tuesday

The Romans named the third day of the week for Mars, their fearless, brutal, relentless god of war. For the Vikings, though, this was Tyr. Tyr was a "god of battles, the foster-father of the wolf, and the one-handed god" (as Snorri says in the Prose Edda). Tyr lost his hand to Fenrir the wolf long ago, but only because he was brave enough and resolute enough to bind the creature. Vikings looked at Tyr as the god of justice. They called his day, Tyr's Day (in Old Norse: Tysdagr). However, our pronunciation comes from Tyr's Anglo-Saxon name Tiw, (hence, Tiwesdaeg). Devoted as it always has been to the god of war, Tuesday is still the day of the week that always seems to be all-business.

Wednesday

The Romans devoted the fourth day to Mercury, the messenger of the gods who traveled across the world with winged sandals. In modern Spanish / French / Italian, the day is rendered as miércoles / mercredi / mercoledì. When the 1st-century geographer Tacitus traveled to Germania (Northern Europe beyond the Rhine), he remarked that the men there worshiped Mercury as the foremost god. But Tacitus had encountered worshipers of the unfamiliar god, Odin (a.k.a. Wotan in Old High German or Woden in Old English). Odin was a traveler, trekking across the Nine Worlds in disguise, searching for wisdom. Mercury was the Roman god of medicine and eloquence, just as Odin was the Norse god of magic and poetry. Our word, Wednesday, comes directly from Woden's Day, or Odinsdagr (as it was in Old Norse). But Odin was such a dreaded and reviled figure to later Christians that in many countries that used to worship him (i.e., Germany, Iceland, etc.) Wednesday was re-interpreted as "mid-week's-day".

Thursday

The Romans devoted the fifth day of the week to Jupiter, also known as Jove. Jupiter/Jove was the same as the famous Greek god, Zeus, and was the king of the gods. For the Vikings, though, the powerful, protective lord of the skies and wielder of thunderbolts was Thor, in which Thursday is named after (Thor's Day). Thor was known to the Anglo-Saxons as Thunar and to other Germanic tribes as Donar. While Thor was not the king of the gods in the Viking pantheon, he was probably the most powerful and the most popular. Interestingly, Tacitus equated Thor not with Jove but instead with Hercules because of the god's strength, bravery, and conspicuous humanity. For many, Thor still retains this superhero aura.

Friday

Of all the theophoric days of the week, Friday is the most controversial. Some assert that Friday is named after the Viking god Freyr. This makes sense because the 11th-century eyewitness, Adam of Bremen, describes Odin, Thor, and Freyr as forming a top-tier of gods that were often worshipped together (including at the magnificent temple at Uppsala). Freyr was a fertility god and god of plenty, and so the Vikings would probably not want to offend him by leaving him out.

Others believe that Friday is not named after Freyr but after his sister Freyja. Freyja was a goddess of war, magic, fertility, and erotic love. Still, others believe that the day is named after Frigg, Odin's wife and the Queen of Asgard. The matter is further complicated: Freyja and Frigg have many overlapping characteristics and may have once even been the same goddess. This ambiguity has long roots, as Friday was called Frigesdaeg in some dialects but Freyjasdagr in Old Norse.

An important clue as to who the day really belongs to can be found by comparing it to the Roman model. For the Romans, the sixth day of the week was devoted to Venus, the goddess of love, beauty, and passion. If the comparison still holds, it would seem that Friday is, therefore, Freyja's Day. We will probably never know for sure, and indeed perhaps our Viking ancestors honored all three on this day.

Saturday

The seventh day is Saturday – the only day in English named for a Roman deity (Saturn) and not a Germanic/Norse one. Saturn has no parallels in Viking lore – except perhaps to the Jötnar (giants) since Saturn was king of the Titans. It is also unusual that Saturn would be left standing, even as a throwback to Roman culture, since he was a strange god and more feared than loved. Since Saturn was the god of time and renewal, though, it may be appropriate that his name is retained for the last day of the week.

The Vikings had their own name for Saturday – and it had nothing to do with gods or goddesses. The Vikings called Saturday Laugardagur, which means "Pool Day" or bathing day. Saturday was the day that Vikings took a bath (whether they needed it or not). This custom, peculiar for its time, was remarked on by observers from England to the East. In Iceland, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, Saturday is still called a form of this name.

Conclusion

Our names of days tell a story of how our various ancestors interacted with each other. Modern peoples are blended from many different cultures. This is especially true of English speakers, whose language and customs still carry the signs of the dozen or so major groups that formed that island nation. Every day is an intrinsic memory of Roman themes interpreted through a Viking lens, then sieved through the medieval church before being more-or-less taken for granted by most people today. When we look at the days' names, we see an example of how things change and how they remain the same.

Sons of Vikings is an online store offering hundreds of Viking inspired items, including Viking jewelry, Viking clothing, Drinking horns, home decor items and more.

To learn more about Viking history, we recommend our 400+ page, self titled book that is available here.

References

- The Poetic Edda. Crawford, J. (translator). Hackett Classics. 2015.

- The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson. Brodeur, A. G. (translator). Retrieved from http://www.redicecreations.com/files/The-Prose-Edda.pdf. Published 1916, Accessed November 3, 2017.

- McCoy, D. The Viking Spirit: An Introduction to Norse Mythology and Religion. Columbia. 2016

- Rodgers, D.G. & Noer, K. Sons of Vikings: History, Legends, and Impact of the Viking Age. KDP. USA. 2018

- Price, N. Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings. Basic Books, New York, 2020.

- Vikings seduced women across Europe. Nordic Culture. 2018. https://skjalden.com/vikings-seduced-women-across-europe/

- Roman calendar. 2020. https://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-calendar.php