Thanks for visiting our blog! As a thank-you, enjoy 15% off your first order in our online Viking Shop with the discount code BLOG15.

When you hear the word ‘Vikings,' an image of hopeless romantics is probably not the first thing that springs to mind. You probably have heard that in the past, most marriages were simply business arrangements between families, and only the poorest people married for love. Some even say that the entire modern notion of romantic love was a whim pioneered by the French Troubadours and Andalusian court poets of the High Middle Ages. It was later refined by Shakespeare before being embraced by the Romantic Poets of the 18th century.

While there are certainly some hard truths within these notions, there is also much more to the story. It stands to reason that people everywhere and across time are more similar than different. While cultural expressions may vary, love could never be a fabrication. It is a visceral force that carries the soul to the highest heights and lowest lows of the human experience. In fact, Viking lore is full of love stories. As hard as their world was and as ruthless as they could sometimes be, they understood and valued this greatest human emotion.

Context and Caution

Entire books have been written on marriage, family, and gender roles in the Viking Age (793-1066). This article is not intended as a sociology/anthropology study, though, so we will brush over some of these interesting topics just enough to provide context.

Like most others in their age, Viking marriages were arranged between families. Unlike most other places, though, the bride (and not merely her father) had to consent. Divorce was even easier in Viking societies than it is in ours. So couples stayed together because they chose to.

Also, unlike other contemporary societies, Norse men and women were free to remarry as often as they cared to. Life expectancy for Vikings was not great. Runestones and saga tales tell of some women being married four or five times.

It was legal and acceptable in most Nordic realms for a man to have multiple wives or concubines. However, for the most part, it was aristocratic or wealthy individuals who would do this. Polygamy may have been one cause of the Viking explosion. Young men would adventure abroad to win enough money to afford escalating bride prices. While they were out there, they may just find a wife in a foreign land.

This brings us to our word of caution: our ancestors' world could be a hard place where many bad people did bad things. Our purpose here is not to pretend those bad things did not happen but rather to look at the good things that also happened.

The Viking Don Juan, as Described by an Annoyed English Clergyman

The Vikings moved seamlessly between raiding and trading. They had plenty of non-violent contact with peoples from Ireland to the Middle East. These Vikings with swagger in their steps and silver in their belts were still not welcome by the local men – even when coming in peace. As one medieval chronicler and monk, John of Wallingford complained of the Vikings:

“… thanks to their habit to comb their hair every day, to bathe every Saturday, to change their garments often, and set off their persons by many such frivolous devices. In this manner, they laid siege to the virtue of the married women, and persuaded the daughters even of the nobles to be their concubines.”

Perhaps it is no wonder then that the chronicles tell of Vikings blending with local populations by the year 840. Vikings may be barbaric brutes in the popular image, but archeology and the written record tell a different story. Instead, Vikings were people who took a lot of pride in themselves, had a lot of confidence, paid attention to adornments, and loved sensory pleasures. They had stories to tell and money to spend. Then as now, these traits often got a lot of attention.

Viking Social Graces

In many traditional societies, women rarely interact with men who are not their husbands or near family members. This was not so in Viking society, where men and women had frequent social exchanges. One typical venue for this interaction was "hall culture" – the feasts, holidays, and mead hall gatherings that formed a building block of Norse society. People would gather to eat, drink, tell stories, brag to each other, tell riddles, play games, network, and fellowship. Women were included in most of these events and played an important role. Men and women had a chance to get to know each other (albeit with the propriety of the public eye). There were occasions to meet potential matches or form other romantic liaisons.

You may remember such scenes from reading Beowulf in school. Many of these events survive vividly in the literary record. It is unusual to find a saga that does not include men and women socializing to romantic or platonic effect. The Eddic poem Havamal captures some of the spirit of these conversations between potential lovers:

“If you want to win a good woman

Speak cheerfully to her

And enjoy it while you do

Make promises to her,

And keep your promises

You’ll never regret winning such a prize”

(v. 130, Crawford 2015 translation)

Such amorous designs did not always work out, though. Elsewhere in the same poem, Odin tells of trying to seduce a beautiful woman he is deeply infatuated with. But he arrives at their pre-arranged meeting time only to be chased off by her armed family. He sneaks back later but finds a vicious dog chained to her bed. “That woman was the love of my heart,” the poet says, “but she exposed me to every kind of shame, and I won no wife for my troubles.”

Love Poems, Love Runes, and Love Spells

Vikings valued poetry, and so it is no surprise that they would turn it to good use in wooing their heart’s desire. We have pieces of these poems sprinkled throughout the sagas and Eddas. We do not have any sonnet-length works like you finds from later years. One reason for this lack of surviving material is that writing love poems to any woman who was not one’s wife was illegal (according to Iceland’s Gragas law codes, distilled from traditional Norse laws). The reason for this was simple: poetry is powerful and so it may bewitch a woman or contain magic that would lead her astray. So, instead of being written down, these poems must have been sung in song or whispered in the lover’s ear.

With matters of love often seeming more significant even than matters of life and death, it is no surprise that some people would turn to magic. There are mentions of love spells throughout the sagas and eddas. Of Odin’s18 spells or powers mentioned in Havamal, two are love spells:

I know a sixteenth [spell]:

if I see a girl

With whom it would please me to play,

I can turn her thoughts, can touch the heart

Of any white armed woman.

I know a seventeenth [spell]:

if I sing it,

the young Girl will be slow to forsake me

(Auden and Taylo 2001 translation)

It is probably for the best that few such spells survive. There are some within the pages of the various Icelandic grimoire (magic books) of later years. The inspiration for some of these may go back to Viking days, but that is impossible to determine for certain.

Some love spells (and love “notes” or poems) were written in runes and “bind runes” (combinations of two or more runes drawn together). Sigrdrifumal (in the Poetic Edda) mentions love-guarding runes carved on a drinking horn, scratched on the back of the hand, or etched on a fingernail. What such runes, bind runes, or symbols might have been was always meant to be a secret, and so there are no Viking Age sources to substantiate whatever might have come down to us through folk traditions.

Love Gods and Love Goddesses

Odin, the chief of the gods, was a war god, god of the dead, a traveler, and a god of wisdom. He was also a prodigious lover. In the Eddic poem Voluspa en Skamma (v.3), it is said the Odin "gives many the happiness of love.”

Freyja is one of the most important goddesses to the Vikings. Like Odin, she was a deity associated with war, magic, and wisdom. She would ride her gold-bristled boar into battle. She claims half of the Valkyrie-chosen battle-slain to serve in her army in Fólkvangr, while Odin took the other half to Valhalla. Freyja was also a love goddess, though. Though the 13th century (Christian) lore master Snorri Sturluson paints her as a devoted wife, all other sources agree Freyja had rampant, unbridled sexuality. She had two daughters, but unlike other Indo-European fertility goddesses, she did not seem to have much of a role in motherhood. Instead, her realm appears to have been the ecstatic, erotic love with all of its glories and dangers.

The Vikings had another goddess named Sjofn, who "was deeply committed to turning the thoughts of men and women to love” (Prose Edda, p.43). Another goddess of love, marriage, and reconciliation is named Lofn (almost certainly where the English word "love" comes from). She was also the patron goddess of forbidden love. Yet another love goddess named Var (which means "Beloved") watched over the oaths lovers made to each other. Var could become angry if these oaths were not kept.

Freyr (or Frey) was one of the most important and venerated of the Viking gods. He was Freyja’s brother (some say her twin brother). Also a Vanir fertility god, adopted into the Aesir, Freyr brought virile male energy into the equation and provided abundant harvests, wealth, peace, and prosperity. Freyr fell desperately in love with the radiantly-beautiful giantess (Jötun), Gerth. Freyr was so lovestruck by Gerth that he traded his magic sword to his servant, Skirnir, to broker the marriage deal. Because Freyr traded his sword for love, he will have nothing to defend himself when he fights the terrifying fire demon, Surt, at Ragnarok.

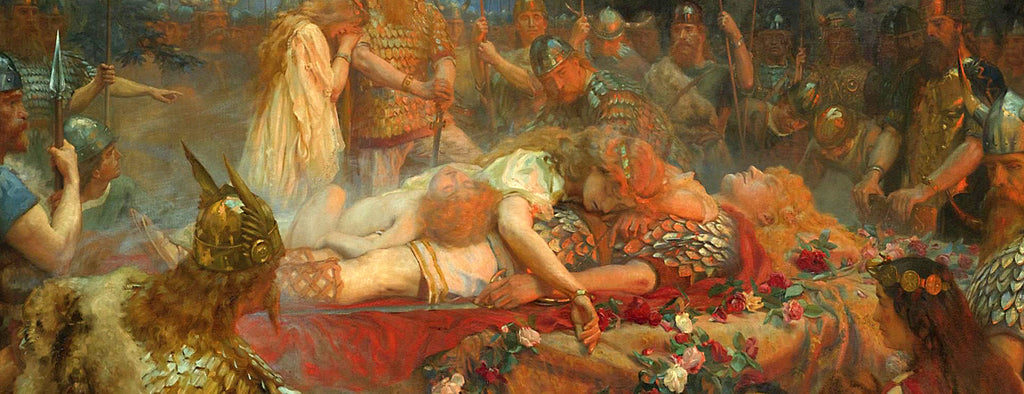

Love Scorned: The Saga of the Volsungs

One of the Vikings' favorite stories was the epic of the Volsung and Niflung (Nibelung) clans. The dynamic relationship between love, fate, and honor forms the central theme in this complex tale of dragons, dwarves, gods, Valkyries, werewolves, and warriors.

In the Vǫlsunga saga version of the story, Sigurd, the dragon-slayer, awakens the cursed Valkyrie, Brynhild, and falls in love with her. They have a child, Aslaug (the future wife of Ragnar Lothbrok). Sigurd becomes friends with the Niflung King Gjuki and his sons Gunnar, Hogni, and Guttorm. King Gjuki’s daughter Gudrun falls in love with Sigurd, and her mother casts a spell on the dragon-slayer so that he will forget Brynhild. Bewitched, Sigurd helps Gunnar win the hand of Brynhild, who had made an oath that she would only marry the man who could cross the wall of enchanted fire that guarded her castle.

Brynhild is bound by her oath and so marries Gunnar. But Brynhild eventually learns she was tricked, and not only has she been deprived of her love, Sigurd, but she has broken her oath, too. Meanwhile, Sigurd's bewitchment wears off, and he realizes that he has betrayed Brynhild. However, he believes the only way for everyone to be happy is to accept their fate and stay in each other’s company as a chaste family.

The collective betrayal of Sigurd, Gudrun, and Gunnar drives Brynhild into full psychosis. The saga paints a compelling picture of mental illness as the Valkyrie turned homebound wife plots her revenge.

Alarmed by her downward spiral, Sigurd confronts her:

Brynhild answers, "Thou knowest me not, nor the heart that is in me; for thou art the first and best of all men, and I am become the most loathsome of all women to thee."

"This is truer," says Sigurd, "that I loved thee better than myself, though I fell into the wiles from whence our lives may not escape; for whenso my own heart and mind availed me, then I sorrowed sore that thou wert not my wife; but as I might I put my trouble from me, for in a king's dwelling was I; and withal and in spite of all I was well content that we were all together. Well may it be, that that shall come to pass which is foretold; neither shall I fear the fulfillment thereof."

(Morris & Magnusson 1888 translation).

These events end in tragedy, and as a result, Gudrun is left with a shattered heart. Her laments (preserved in the Poetic Edda) are some of the most moving passages in Norse literature. Gudrun is eventually ruined by these events, and she lives the rest of her days in alienation and wrath.

Tragic love: The Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-Tongue

Many other tales of Viking romance have passed down to us through the Íslendingasögur (sagas of Icelanders), the more realistic (i.e., fewer dragons) stories from the period. One of the best known of these is the Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-tongue. Gunnlaug is a Viking poet whose words wind sinuously like a beautiful serpent. He falls desperately in love with Helga, essentially his childhood sweetheart. But his friend and competitor, the poet Hrafn, also loves Helga. Hrafn is the more well-connected and preferred by Helga’s father. Gunnlaug travels the Viking world trying to earn enough money with his sword and poetry to earn Helga’s hand. But while he is gone, Helga’s father gives her to Hrafn. Because Helga is deceived into thinking Gunnlaug left her, she reluctantly agrees to the marriage.

Gunnlaug returns with enough wealth to secure Helga, including a gorgeous red cloak from the King of Dublin. But he finds Helga married to Hrafn, and all happiness rapidly unravels. Helga still loves Gunnlaug, and as the saga observes, “If a woman loves a man, her eyes won’t hide it.” But as in the Volsung Saga, honor intervenes and prevents action.

Increasingly sorrowful and angry, Gunnlaug sings,

For Serpent-tongue, no full day was easy since Helga the Fair was called Hrafn’s Wife.

But her father, white-faced wielder of whizzing spears, took no heed of my tongue – the goddess was married for money.

Soon, neither Gunnlaug nor Hrafn can take it anymore, and they challenge each other to a duel. This duel became the last duel ever fought in Iceland. It was considered so horrible that duels were made illegal ever after. However, neither of the men win. Still unable to accept the stalemate, Gunnlaug and Hrafn, along with some of their loyal friends, travel to the Orkney Islands to battle there.

In that fight, Hrafn is badly wounded. Gunnlaug has mercy and stops his attack. Hrafn begs his old friend for water, and as Gunnlaug fills his helmet from a stream and brings it to him, Hrafn strikes Gunnlaug a mortal wound. As Gunnlaug dies, he accuses Hrafn of shameful betrayal. Hrafn (also bleeding to death) says that he cannot bear to think of Helga leaving him, even in death.

The saga ends with a devastated Helga eventually marrying a good man named Thorkel. She bears him children and keeps house. But she is racked with depression and spends long hours sitting and staring at the cloak Gunnlaug gave her. Years later, during a deadly epidemic, Helga lies her head on Thorkel’s lap, Gunnlaug’s cloak in her hands, and silently dies. Thorkel lives the rest of his days in sorrow.

Lifelong Love

The sagas and poetry of the Vikings are replete with lasting, lifelong love as well. Saga heroes like Njal and his wife, Bergthora, are strong couples that make for strong families. Other power couples of the age include Eric Blood-axe and his notorious wife, Gunnhild.

But life was hard and often short. In poetry, heroines yearn to follow their war-slain lovers into the afterlife so they will not be without them. Meanwhile, the more down-to-earth sagas tell tales of widows and widowers forging ahead after their loved ones' deaths.

One example is Aud the Deep Minded, the widow of Olaf the White. Aud built ships in secret (hiding from her enemies) and led her clan to Iceland. There she freed her slaves and became one of the great community leaders in those pioneer days.

Another example is Ragnar Lothbrok, whose exploits outside of Norway and Denmark accelerated after the death of his most beloved wife, Thora.

The reality was that life went on, and so – as mentioned earlier – runestones and sagas tell of women outliving multiple husbands. One of the most popular of all Icelandic Sagas (as proven by many surviving manuscripts) is the Laxdæla saga (Saga of the People of Laxárdalr). Laxdæla saga tells of a love triangle between the high-spirited woman, Gudrun Ósvífrsdóttir, and two men, Kjartan Ólafsson and Bolli Þorleiksson. Gudrun (different from the Volsung Saga Gudrun) lives a long life and ultimately marries four times. Towards the end of this saga, her daughter asks her which of her husbands she had loved the best. With all the regret of age, Gudrun answers cryptically, "To him I was worst whom I loved most.”

Nothing was certain or fully under human control in the wild world the Vikings lived in. They believed everything was in the hands of fate. In many ways, this made the love they found sweeter, more sublime, more painful. This is reflected in their lore and poetry. Then as now, love is the strongest of human emotions and one of the best parts about being alive. At least, the Vikings thought so.

Sons of Vikings is an online store offering hundreds of Viking inspired items, including Viking jewelry, Viking clothing, Drinking horns, home decor items and more.

To learn more about Viking history, we recommend our 400+ page, self titled book that is available here.

Images:

Lovers and Siegfried. 1911. Artist: Arthur Rackham

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur_Rackham_Lovers.jpg

Freya (Freya seeker her husband). 1852. Artist: Nils Blommer. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freyja

Sigurd and Brynhild (funeral of a Viking warrior). 1909. Artist: Charles Ernest Butler. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sigurd_and_Brynhild,_C._Butler_1909.jpg

Waltraute (the Valkyrie) confronts her sister Brünnhilde (Waltraute Confronts). 1911. Author: Arthur Rackham. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waltraute_confronts.jpg

References

- The Saga of the Volsungs. William Morris and Eirikr Magnusson (Walter Scott Press, London, 1888. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1152/1152-h/1152-h.htm#link2HCH0029

- The Poetic Edda. Crawford, J. (translator). Hackett Classics. 2015

- Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda. (translated by J. Byock). Penguin Classics. London, England, 2005.

- The Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-tongue. Attwood, K. (translator). The Sagas of the Icelanders (editor, Thorson, O. & Scudder, B.) Penguin Books, New York, 2001

- Saxo Grammaticus. The Danish History. Circa 12th Century. Retrieved January 4, 2018, from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1150/1150-h/1150-h.htm

- Rodgers, D. & Noer, K. Sons of Vikings: History, Legends, and Impact of the Viking Age. KDP. United States. 2018.

- Price, N. Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings. Basic Books, New York, 2020.

- The Saga of the People of Laxardal (K. Kunz, translator). The Sagas of the Icelanders (editor, Thorson, O. & Scudder, B.) Penguin Books, New York, 2001

- Havamal (Sayings of the High One). W.H. Auden & T.B. Taylo (translators). 2001. http://www.public-library.uk/ebooks/43/74.pdf