Thanks for visiting our blog! As a thank-you, enjoy 15% off your first order in our online Viking Shop with the discount code BLOG15.

How the Vikings in France Became One of the Greatest Powers of the Middle Ages

The Normans – the offspring of Viking raiders and the indigenous population along the west coast of France – became one of the Middle Ages' biggest influences. Their ingenious political machinations and supreme military formed a power that offset the Holy Roman Empire, the Byzantines, and the Caliphates of the south and east. They controlled lands from Ireland to Jerusalem. Some of the most colorful and notorious characters of the age – Rollo the Walker, Robert the Crafty, William the Conqueror, Bohemond the Crusader, Richard the Lionheart, and more – were from their ranks. Even today, their progeny sits on the English throne, and their laws, language, institutions, and ideas are everywhere we look. This article briefly recounts their story.

The Carolingian Empire and the Vikings

In the 8th century, Europe began to recover from the economic depression, political chaos, demographic upheaval, and rampant war of the Dark Ages. One of the driving forces in this return to order was the Frankish ruler, Charlemagne. Through tireless energy, boundless vision, and ruthlessness, Charlemagne forged an empire in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy. The powerful Caliphates to the South and East respected him, the Byzantines of the Mediterranean and Balkans resented him, and his pagan neighbors of northeastern Germany and the Baltic feared him.

But even as he was being crowned by the Pope as the emperor of a new, Holy Roman Empire, the wealth and sophistication of Charlemagne's realm was an irresistible lure to Vikings. These dragon ship raids were small, fast, and sporadic while the great man was alive, but when Charlemagne died in 814 and was replaced by Louis the Pious, the raids increased.

When Louis died, he split the rule of the vast Carolingian Empire amongst his sons to keep the peace. This split did anything but keep the peace, though. The sons were in constant competition and sometimes open war with each other. From the waves, the Vikings saw the disorder and realized that their time had come.

Beginning in the 830s, Viking raids grew exponentially. These were no longer expeditions of a few ships but were now dozens – or even hundreds – of ships with hundreds – or even thousands – of Vikings. Worse yet, as time passed and chaos grew, the Vikings switched from seasonal raids to overwintering in the countryside as semi-permanent but highly mobile armed communities.

The Vikings used the river systems to access the land's wealth and attacked bigger and bigger targets. Ragnar Lothbrok besieged Paris itself in 845. Bjorn Ironside occupied the Loire Valley in the late 850s. By the 860s, according to Frankish chroniclers, there was barely a city or monastic center that had not been attacked.

All the while, the grandchildren of Charlemagne were too preoccupied with each other to fight the Vikings. When they did, they were easily beaten. Sometimes the various Carolingian rulers would even hire the Vikings to make war on their neighbors. As in the case of Ragnar's siege of Paris, the Franks decided it was safer to pay the Vikings to go away than it was to fight them. These payments were known as danegeld (literally, money to the Danes). The danegeld would add up to a massive amount of money. Archeologists have found tremendous amounts of Frankish silver in Scandinavia. Historians have determined that the cash lost in danegeld equaled about 14% of the entire Carolingian economy for a whole century! This is in addition to the vast amount of plunder and movable wealth the Vikings seized in their raids.

Rollo the Walker

In the mid-9th century, a prominent nobleman’s son was exiled from Norway for stealing King Harald Fairhair’s own cattle. This brazen young man was called Rolf Ganger, which meant Rolf "the Walker" because he was allegedly so big that he couldn't find a horse to ride. Rolf Ganger went to Scotland and later participated in the Great Heathen Army that invaded England in 865 (he is mentioned explicitly in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). But when Alfred the Great made peace with the Vikings around 878, Rolf led a large force of Vikings back into France and resumed raiding along those coasts and riverways. In Frankish sources, this new Viking leader would be called "Rollo," and he was destined for great things.

By 885, Rollo had amassed enough of a following to besiege Paris. This siege lasted for nearly two years and only ended when the Vikings were paid off with an enormous sum. Even then, they did not leave France but kept following their fortunes up and down the river systems of the Seine, Somme, Rhone, and Loire.

Finally, in 911, the latest Frankish King, Charles the Simple, decided to deal with the notorious Rollo the only way he could. Charles granted Rollo and his Vikings a large swath of prime land (much of the northwestern coast, in fact) if they would just settle down and guard his realm against other Vikings. To sweeten the deal, Rollo was offered the title, Count of Rouen; and to make the deal irresistible, he was offered the hand of Charles’s daughter Gisele in marriage. The notorious, invincible Viking was about to become the King’s son in law.

There were many catches, of course. Rollo and all those loyal to him had to stop plundering, and their leaders had to be baptized as Christians. But for Rollo, this was a price he was willing to pay because he knew there would be plenty of opportunities for wealth and glory by shifting his perspective elsewhere.

Rollo was baptized, married, and anointed Count of Rouen by 912. His Vikings immediately started defending their new turf from other Vikings and threats from all directions. The land was closest to England and right along the main continental (Viking) raiding route south from Scandinavia. As a direct result, this land became known as Normandy. Medieval Latin documents referred to them as Nortmanni, which means "men of the North". Eventually, the Count of Rouen took the grander title, Duke of Normandy.

From Northmen to Normans

Judging by their actions, it was not just Rollo who knew he had been given a golden opportunity. It was all of the Vikings under his command. Very rapidly over the next decades, these Vikings would change in many ways while retaining many of the essential aspects of the character that had made them so successful.

The Vikings knew that if they just remained a separate military elite in Frankish lands, they would be easily cast away when their usefulness had ended. Instead, they conscientiously took French wives, learned the Frankish (and sometimes Latin) tongues, and became patrons of the Church. While the aristocrats of Europe may have been looking down their long noses at these barbarians, the Vikings were busy becoming something new: they were becoming Normans.

The change from Northmen to Normans was not only a matter of cultural adaptation, though. The Vikings took full advantage of the resources, technology, and techniques of their former enemies.

In the things that mattered most, the Normans still fought like Vikings. That is, they had an indomitable spirit. Though Heaven had replaced Valhalla, Medieval history is replete with tales of Norman valor. They also kept (and even refined) the Viking love of cunning and strategy. They continued to love the dragon ship (though the dragon head eventually disappeared) and all manner of naval and marine warfare. Like their Viking ancestors, they launched bigger and bigger expeditions, including some of the largest overseas invasions before modern times.

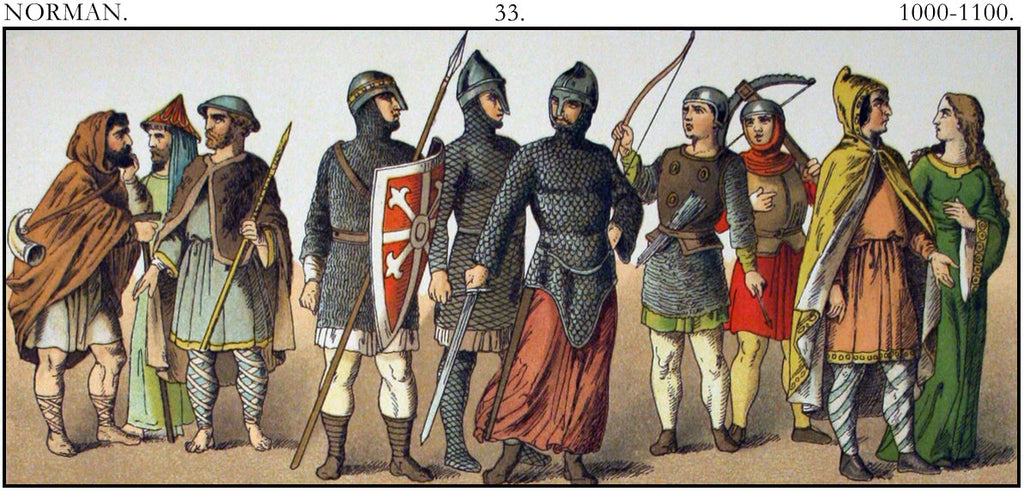

On land, though, their method of warfare exhibited a few essential changes. Unlike the 9th century Vikings, the Normans finally had access to more standardized resources. The Bayeux Tapestry shows largely-uniform warriors, wearing heavy hauberks of steel armor – scales and mail – and simple, standardized helmets with nose guards. These "Norman helmets," as they have become known (even though period art also depicts Vikings wearing them), were conical so that blows would glance off them.

The Norman sword would gradually become longer than the Viking sword had been. It was still a one-handed weapon because of the shield's importance, but the blade shape would change to a sharp, armor-piercing tip. It also developed the longer cruciform cross guard standard of high medieval swords.

The center-gripped circular shield was replaced by a larger, strapped shield that was shaped like an inverted raindrop. This change in shield reflected the most significant change in the Norman war machine – reliance on heavy cavalry.

Hitherto, the Vikings had not been cavalrymen. After the embarrassment of Paris's first siege, Charles the Bald reinvigorated heavy cavalry to catch and kill Viking warbands. The Normans now embraced mounted warfare and became some of Europe's best knights. The aristocracy based on owning and using horses in war goes back to Roman, Germanic, and Eastern peoples, but it was now reborn. With his high-stepping charger, shining armor, long lance, and code of chivalry, the medieval knight is perhaps the most enduring image of the Middle Ages. The Normans threw themselves into this role and helped define it for ages to come.

Another significant change in the Norman mode of warfare and dominion can still be seen throughout Europe and the Middle East today – castles. The Normans did not invent castles, and their Viking ancestors certainly understood the importance of fortifications. Still, the Normans would use castles built of stone to systematically secure and control the many lands they conquered. The Normans built more castles during their time on the world stage than anyone else. For the subjugated peoples from Ireland to Syria, the Norman castle became both a hated symbol of their overlords and an effective deterrent to rebellion.

And so, reinvented and re-equipped, the Norman descendants of Rollo’s Vikings were ready to make an impact on their world in a way that few had. For if the Franks had thought that the Vikings would merely settle down, they had been wrong. The wanderlust, daring, and thirst for adventure still burned inside the Norman's heart, and it was about to cause an explosion of action in every direction.

Expansion

Throughout the early 11th century, as the Viking Age was waning, Norman mercenaries were fighting in Italy and the Mediterranean. First, they fought for the Lombards – but then they began to also fight for the Byzantines. As their numbers grew, and they started taking their payment in land, they began fighting for themselves.

The tipping point occurred in 1053 when the Pope himself led an army against the Normans to stop their meddling and curb the mayhem they were causing throughout Italy. It was a disaster. The Pope was captured and placed under Norman "protection." The Normans returned him to his papal seat in Rome, but only after extracting terms that were very much in their favor.

After that, the Italian strategy turned from trying to crush the Norman power-usurpers to trying to contain them. In 1059, Robert Guiscard – or Robert the Crafty – was granted the hitherto-nonexistent dukedom of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. This gave the Normans the southernmost extremity of Italy (which they already controlled) and the island of Sicily – the very powerbase of the aggressive Saracen Moors. This was clearly a suicide mission.

But if they were being set up to fail, Robert and his Normans had been badly misjudged. Byzantine princess Anna Comnena, daughter of Robert’s arch-enemy, offers this description of him:

This Robert was a Norman by birth, of obscure origin, with an overbearing character and thoroughly villainous mind; he was a brave fighter, very cunning in his assaults on the power and wealth of great men; in achieving his aims absolutely inexorable, diverting criticism by incontrovertible argument. He was a man of immense stature, surpassing even the biggest men; he had a ruddy complexion, blonde hair, broad shoulders, eyes that all but shot out sparks of fire…Homer remarked of Achilles that when he shouted his hearers had the impression of a multitude in uproar, but Robert’s bellow, so they say, put tens of thousands to flight.6

And so it was that as Robert was given military opportunities, he took them and he won. He combined cunning strategy with the devil’s luck, and he climbed meteorically. With the help of his younger brother, the patient and wise Roger, Robert conquered Sicily and mopped up the remainder of Byzantine control in Italy within just a few years.

Robert’s keen military skill and cunning combined with Roger’s policies of tolerance and his ability to win over Muslim, Greek, and Italian populations. This enabled the Normans to not only take dominion of the Sicily, but to take it over as a whole and still productive property. There were no reigns of terror or costly rebuilding periods. In fact, Robert always had more trouble dealing with his rebellious Norman barons' independent spirit than he did from his conquered peoples. Sicily was immediately a source of trade wealth and allied forces. It would go on to be one of the most prosperous kingdoms of the Middle Ages.

Meanwhile, back in Normandy, Duke William "the Bastard" audaciously pressed his (somewhat shaky) claim to the English throne against the Saxon-Danish elected ruler, Harold Godwinson, and the hell-raising Viking king of Norway, Harald Hardrada. William (a 5th generation descendant of Rollo) launched a massive fleet of Normans, Franks, and Bretons. He crossed the channel just as the English and the Vikings were annihilating each other at the epic battle of Stamford Bridge near York.

A few weeks later, the English met the Normans at Hastings on a fateful day in 1066. English history was forever changed. William exchanged his pejorative nickname and became William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy and King of England. His descendants have kept the throne of England ever since.

By the late 11th century, Normans held realms in England, France, Italy, and Sicily, but they were not done yet. Over the next century, the Normans would establish control over Wales, Ireland, and sometimes Scotland. In the Mediterranean, Robert Guiscard and his son, Bohemond, fought the Byzantines of Greece, Turkey, and the Balkans. Then, in 1096, the Normans found themselves at the helm of one of world history's biggest movements. The Crusades had begun.

For the next few hundred years, Normans joined Europeans from many countries to launch large invasions of “the Holy Land.” This was supposed to be a pan-Christian movement to return lands in Palestine, Israel, Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere to Byzantine control. While many of the Crusaders showed religious fervor, lords like Bohemond were also looking to carve out territories of their own in these fabled places at the heart of world trade. As these dramatic events played out, Normans formed "The Crusader States," such as Antioch's Principality and the Principality of Tripoli.

Later, the Norman king of England, Richard the Lionheart (1157-1199), would become one of the most renowned figures of the Crusades and be immortalized in legends like Robin Hood and literary works like Ivanhoe. His triple lion heraldic sign is still recognized as a symbol of England today.

A Norman would not sit on the throne of Jerusalem until Frederick II (son of a German emperor and a Norman queen) united the Kingdom of Sicily, the Crusader state of Jerusalem, and the Holy Roman Empire in 1225. Frederick II was a character large enough to make this happen, but the situation was too precarious to survive him. In any case, the Normans combined military and political acumen with boundless ambition. They seemed to be everywhere at once throughout the Middle Ages.

Legacy

The Normans set into motion many of their day's political, social, economic, military, and cultural changes. They changed the course of medieval history on many occasions. Today, their legacy is still evident. One example of this is the English language. The large number of French and Latin roots and cognates in English was from the Norman takeover of Britain after 1066. It is no accident that many of these words sound educated or fancy. In contrast, shorter, more direct words tend to be of Anglo-Saxon origin. This reflects the Norman aristocracy superimposed upon the Anglo-Saxon and Danish population.

The Normans also left a significant mark on the politics of all free modern societies. In 1215, Anglo-Norman barons met with King John (formerly Prince John of Robin Hood infamy) and forced the King to sign the Magna Carta. This “Great Charter” was the first formal attempt to officially and permanently curb the power of a medieval king by establishing that the Throne, too, is subject to the Law. It speaks of the rights of “free men” and lays the groundwork for all later English and American jurisprudence.

These barons, with their strong sense of personal pride and independence inherited from their Viking forefathers, put their very lives on the line to ensure that their progeny would live in a land where no one was above the law, and the reckless actions of one man would not be able to go completely unchecked. It would be a long road between the Magna Carta and the constitutions of modern free nations, and indeed more is still being done – but it is interesting to think that it was the descendants of Vikings who got it all started.

Curious about your ancestor's true heritage?

Most people know where their grandparents are from, but where are THEIR grandparents from? You might be surprised. DNA test results have come a long way and can now trace the various journeys of your ancestors going back over a thousand years. For quality results (the most comprehensive ancestry breakdown on the market), we highly recommend using 23andMe. Please note that if you end up making a purchase, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Sons of Vikings is an online store offering hundreds of Viking inspired items, including Viking jewelry, Viking clothing, Drinking horns, home decor items and more.

To learn more about Viking history, we recommend our 400+ page, self titled book that is available here.

References

- Rodgers, D.G. & Noer, K. Sons of Vikings: History, Legends, and Impact of the Viking Age. KDP, USA. 2018

- Bronworth, L. The Normans: From Raiders to Kings. Crux Publishing, USA. 2014.

- Bronworth, L. In Distant Lands: A Short History of the Crusades. Crux Publishing, USA. 2017

- Howarth, D. 1066: The Year of the Conquest. Penguin Books, USA. 1984.

- Daileader, P. The Early Middle Age. The Great Courses by The Teaching Company, USA. 2013.

- Norwich, J. J. Byzantium: The Apogee. Knopf, UK. 1992.

- Price, N. The Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings. Hatchet Book Group, New York, 2020.

Image Sources

Wikipedia